By John F. Di Leo, Opinion Contributor

When California Democrat Governor Gavin Newsom announced his nominee to fill the late Democrat U.S. Senator Dianne Feinstein’s unexpired Senate term, one would have expected the nomination to raise some eyebrows.

On the issues, he picked a garden-variety modern leftist extremist, very much a typical candidate for the current Democratic party.

Newsom’s pick — Laphonza Butler has been a union boss and an abortion lobbyist.

She’s worked for a Kamala Harris campaign.

She supports the destruction of big city policing that George Soros requires, and she checks off the demographic boxes – black, female, lesbian – that the rest of the Democratic donor community requires.

So there should be little surprise in the nomination. One would expect it to sail through, especially since – if she doesn’t campaign to hold the seat next year – it gets the governor out of having to choose sides in a challenging primary battle already brewing for 2024 — if, on the other hand, Butler does decide to campaign to hold the seat, Newsom will have created quite a trap for himself.

That being said, her nomination did create a rather shocking scandal, when it dawned on the public that the newest Senator from California doesn’t actually live in California at all.

For over two years now, she has lived in Maryland.

That’s right. California’s newest U.S. Senator lives in Maryland.

In 2018, Democrat Governor Jerry Brown appointed Laphonza Butler to a twelve-year term as a member of the board of regents of the University of California. Having served less than a quarter of her commitment on this prestigious post, she was named president of Emily’s List, one of the nation’s main single-issue PACs devoted to electing radical abortion extremists to public office.

And for this particular job, she moved to Maryland in 2021.

For over two years, therefore, the new U.S. Senate nominee from California has lived in the state of Maryland. She’s been registered to vote there since 2021.

She is therefore ineligible for the position.

This isn’t a matter of opinion. It’s not open to debate at all. It’s a simple fact.

In establishing the qualification rules for the U.S. Senate, the Constitution of the United States, Article I, Section 3 says the following:

“No person shall be a Senator who shall not have attained to the Age of thirty years, and been nine Years a Citizen of the United States, and who shall not, when elected, be an Inhabitant of that State for which he shall be chosen.”

Those who like to play games with language, parsing words and such – along the lines of the famous Clinton line, “It depends on what the meaning of ‘is’ is” – can easily imagine a loophole here. “She just has to re-register in California, that ‘s all! That’ll just take ten minutes at City Hall. She can probably even do it remotely, on a Zoom call from her house in Maryland…. Er… well, maybe not that…”

But for those of us not inclined to play games, the meaning of the Constitution is clear. The state can choose anybody in the state who’s been a U.S. citizen at least nine years and lives there at the time of the appointment.

This isn’t a difficult bar to reach. California has 40 million people in it, at least half of whom are probably legitimate US citizens. And of those, more than half are certainly Democrats. Take out the children and young adults, and we still have somewhere between five and ten million Democrats who are eligible to fill Dianne Feinstein’s U.S. Senate seat.

Why, then, did Governor Newsom have to leapfrog over all those millions of local Democrats to give the job to somebody across the continent? Someone, in fact, who just two years ago, displayed her devotion to the people of California by leaving a plum statewide appointment only a quarter into it, to move 3000 miles away? Is this the type of person the voters should trust to represent them in Washington?

Your typical Democrat may not see a difference here, thinking that one rubber stamp for Bidenomics is much the same as any other rubber stamp. If Dianne Feinstein could do the job in the utter infirmity of her final years, surely anybody could, right?

But Democrat politicians should see the difference. And non-Democrats too should be astounded by the implications.

It comes down to two things: what representative government is all about, and what the Senate is really for.

First, let’s look at what representative government is all about.

There are a few countries in the world with what they call “at large” voting districts for their national legislatures. Israel’s Knesset, the Philippines’ Senate, and the Netherlands’ House of Representatives, do not have districts as we do in the USA; they hold a national plebiscite, and the parties who win a share of the seats appoint their most senior members to as many seats as they win. This could conceivably mean a broad geographical distribution across the country, but it often doesn’t. Often, it means that most of the legislators come from the same few big cities. It means that people outside those big cities lack representation by people who know their circumstances well. It means that some areas may be well-represented, and others may not be represented at all.

By contrast, here in the United States, we reserve that “at large” approach for smaller local elections such as school boards and park boards. Most other legislatures, from the county level to the state and federal, are all carved into maps, so that even if the person elected to represent you is from another party, he or she is at least likely to have shared experiences with you, enough appreciation of the nature of your shared region that if people who don’t know your area propose something that would be awful for you, there’s somebody in that assembly who will recognize the danger and will be empowered to speak up and stop it.

So for this reason, there are two members in the Senate from California, two from Oregon, two from Washington, two from Alaska, and so forth for all fifty states. The bigger our government gets – the more intrusive, the more powerful, the more ambitious – the more important it becomes that we all have someone there who’s looking out for us.

Second, let’s look at what the Senate does, in particular.

In addition to the jobs it shares with the House, such as budgetary matters like taxing and spending, the Senate must approve or deny every treaty that a President negotiates. The Senate must approve or reject every federal judge or Supreme Court Justice the President proposes. The Senate confirms cabinet members and undersecretaries, major agency chiefs and the superiors of each branch of the military.

The President can only propose; the Senate gives a yes or no.

While it’s possible to take the easy way out and assume that this “advice and consent” is ceremonial, the fact is, a great deal of inside knowledge is expected from the Senate on this point.

Remember the original design, before the XVIIth amendment ripped up the Framer’s plan. Senators were not to be politicians directly elected by the voters; they were supposed to be elder statesmen, well-known in their respective state capitals.

Our original plan – which lasted 120 years – was for the Governors and Legislatures of the states to name their two champions – the wise, experienced statesmen who would recognize when Washington DC was overstretching past its bonds, so they could cut it back at the start.

The Framers intended for the Senate to be the state governments’ eyes and ears, watchtowers and guard dogs, supervising the city of Washington DC.

The Framers knew that our nascent nation was already too big in the 18th century for one executive to know enough politicians across the country to fill all the posts in this executive branch with confidence. The President would count on the Senators – who presumably knew all the people of importance in their respective states – to stop a bad appointment if someone’s charm and impressive resume had successfully conned our President.

If the President appointed someone who had exaggerated his resume – or who was involved in antics back home that would soon become embarrassing on the national stage, or who had been great in his youth but recently became riddled with addictions, mental illness, or other challenges – then the Senators from his or her home state would be more likely to catch such an error and stop the nomination, sparing the country the embarrassment.

This is what the Senate is for. This is why geographical restrictions such as residency requirements truly have value.

We are stuck with the XVIIth Amendment, unfortunately. It’s not going to be repealed anytime soon. But we can, and should, remember the pre-XVIIth purpose for the original configuration of the Senate, and try our best to continue to fill it with the kind of stateman that our Framers intended for it. Hyper-partisan they may be, but at least we can demand that they be from the states they are appointed to represent.

Back, now, to the concept of residency requirements.

The Framers knew there would always be some geographical movement in our growing country. A businessman might spend time in a distant port, a distant city, a distant farm, perhaps for a year or two or three. While they understood this, they recognized that such absences would reduce the ability of a Senator to perform the tasks described above, so they instituted these residency requirements.

Only someone currently an inhabitant of a state, at the time of the selection (whether it be a public election, a Governor’s appointment, or a state legislature’s vote) could be considered for the office. Not a week or a month later, when a far-off politician can simply rent a room or buy a P.O. Box, but at the first moment of consideration for the appointment.

After all, what was our Framers’ greatest fear about this new government they were designing? That it would take on a life of its own, that it would lose touch with the local people back home, that the representatives would forget the needs and rights of their old colleagues in Albany or Richmond or Philadelphia or Providence.

The Framers’ feared that Washington would become what we call it today – a swamp – filled with a local bureaucratic class that owes its allegiance not to the people of the fifty states, but to their governmental and quasi-governmental comrades – both in the federal bureaucracy and in the NGOs that dance with it.

And what, now, is Governor Newsom’s pick for the US Senate? A woman whose tightest bonds are clearly with the national labor unionizing movement and the national abortion mill industry, all centered on the East Coast, three thousand miles from Sacramento and her intended constituents.

It’s too late to stop the nomination. The Democratic Party’s disinterest in obeying the requirements of the Constitution should by now be self-evident.

But the United States Senate could, in a rare moment of lucidity, refuse to seat her.

Any politician should be able to tell that if you don’t have to live in the state you profess to represent, it’s only a matter of time before both houses of Congress are populated entirely by the bureaucrat class of Washington DC.

Will a majority of the current Senate be sharp enough to understand this threat to their very existence? Probably not. But it’s worth noting that the possibility exists; even today, we can’t say that the Framers didn’t give us a path out of our challenges, if only we had the sense to take it.

Copyright 2023 John F. Di Leo

John F. Di Leo is a Chicagoland-based trade compliance trainer and transportation manager, writer, and actor. A one-time county chairman of the Milwaukee County Republican Party, he has been writing regularly for Illinois Review since 2009. Follow John F. Di Leo on Facebook, Twitter, Gettr or TruthSocial.

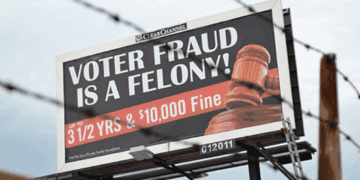

A collection of John’s Illinois Review articles about vote fraud, The Tales of Little Pavel, and his 2021 political satires about current events, Evening Soup with Basement Joe, Volumes One and Two, are available, in either paperback or eBook, only on Amazon.

Don’t miss an article! Use the free tool on this page to sign up for notifications whenever Illinois Review publishes new content!