By John F. Di Leo, Opinion Contributor

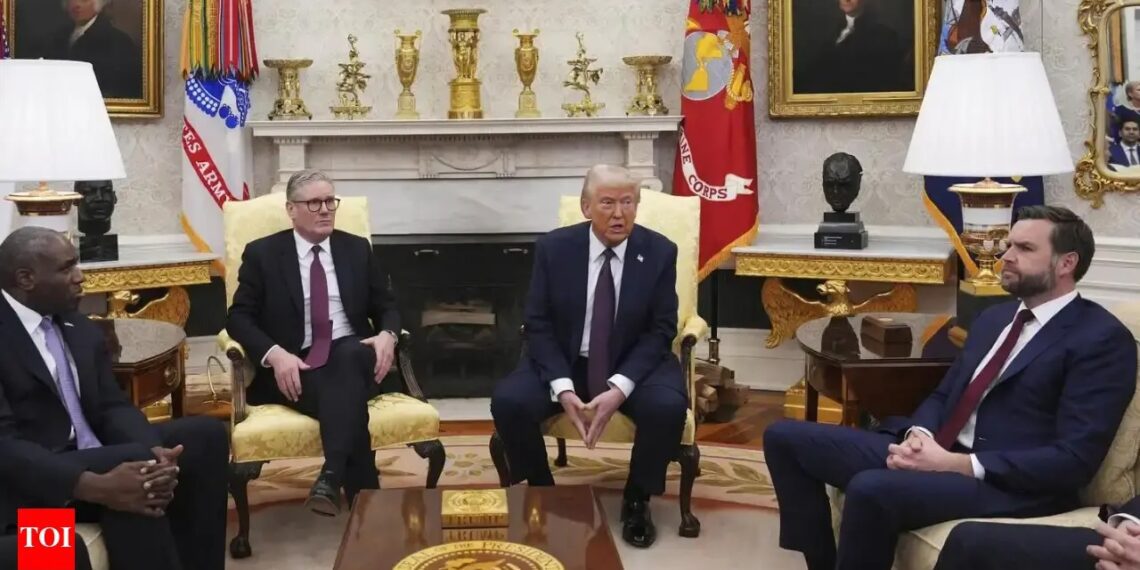

Vice President Vance has informed British Prime Ministert Keir Starmer that fixing Great Britain’s outrageous constraints on free speech will be a requirement to achieve a trade agreement between the U.S.A. and the U.K.

Philosophically, this should be a given. The very worldview of our Founding Fathers was largely based on the Scottish Enlightenment thinkers, and their view that the protection of free speech is fundamental to both responsible governance and a civil society.

If Great Britain, obviously the home of the Scottish Enlightenment and the primary model for our own country’s design, has strayed from that path – and yes indeed, it has – then it makes sense for us to use our leverage to get Britain to restore its once proud position as a champion of free speech.

But we hear voices of dissent. “That’s not what a trade agreement is supposed to address!” “These deals are supposed to be about goods and money and commodities and technology, not about philosophical questions!”

And perhaps most offensively, “What right do we have to tell them how to write their internal rules about speech protections? It’s none of our business!”

The dissenters are right about one thing: these trade agreements usually aren’t about speech. They usually don’t get into this sort of thing.

But that doesn’t mean the usual way is right.

The Trump agenda, especially in this second term, has been all about stressing the fact that much of the way that governments have been doing business lately has been terribly wrong, and requires correction.

With the USA having the reputation as the City on a Hill – the world’s role model for good government – we do have an obligation to use our position and our leverage to try to correct the wrongs that we can correct, at least where such correction serves the interests of the United States.

Trade agreements do, however, frequently get into issues of internal, domestic law. They do so all the time.

For example:

We require that a trading partner must not use child labor in dangerous sweatshops, both because it provides an unfairly low cost advantage and because it’s morally right to ban such practices.

We require that a trading partner must honor patent, trademark and copyright protections, both because it’s critical to the development of new products and technologies, and because it’s morally right to preserve property rights, especially intellectual property.

We require that a trading partner must not use slave labor, both because such enslavement of religious or ethnic minorities (or any other form of involuntary servitude) provides an unfairly low cost advantage and because it’s morally right to stand up for innocent and abused populations.

If we wield the leverage of billions – or even hundreds of billions – of dollars in annual trade, we do have a moral obligation to put that leverage to noble use. This doesn’t mean meddling with all the internal affairs of another nation; it means making sure that the trade in which we participate is honorable enough that we can be proud of both our exports and our imports.

But, does freedom of speech belong in that class of issues?

The mainstream press has been using carefully-chosen examples to illustrate how irrelevant they claim this issue is to the United States. Their examples include incidents involving British speakers, British demonstrators, British abortuaries, British courts. They say this is an internal matter; America should leave it alone, since no Americans are involved.

But Americans travel to the United Kingdom, just as UK citizens do, and will continue to, travel to the United States. In person. Putting themselves at risk, if these speech controls aren’t corrected.

As a fellow English-speaking nation, we have always had an enormous amount of travel between us. Students in college or grad school, families on vacation, retirees with a second home. We see everything from singles traveling alone to tour groups with hundreds all together, flying “across the Pond”, as they visit, respectively, “the colonies” or “the mother country.”

Recent cases terrify such prospective travelers. The lines need to be drawn, clearly and sensibly.

The USA sensibly maintains that a foreign student on a student visa who takes advantage of our freedom and works to organize on behalf of a foreign terrorist organization (Hamas), and leads a violent attack on his school’s buildings and students, should be returned to his home country. The US maintains that such an act of violence is not protected as speech.

Some in Britain are just as vehement that a woman – quietly standing near an abortuary, not saying a single word, not raising a hand in anger, just peacefully carrying a sign that says “Here to talk, if you want” in hope of saving a baby’s life – deserves to be fined or jailed or bankrupted by legal fees. The U.K. maintains that even though this is clearly just speech, it doesn’t deserve protection.

The Left’s position on both examples – allowing violence if they agree with the terrorist’s goal, while criminalizing peaceful speech that they disagree with – is terribly destructive to both commerce and society as a whole.

We need to understand the lines that a nation draws between speech and action. We need to be confident that both speech and the speaker are protected, and that violent attackers, whatever their motivation, will be prosecuted. The defense of the innocent and the prosecution of the violent are fundamental to Western Civilization, so they do belong in any trade deal.

Think of this from the perspective of the businessman – from either country – who flies to the other one on a business trip, ready to negotiate contracts, supervise the quality practices at a plant, manage a factory, or take prospective customers or vendors to lunch or dinner, to negotiate prices or contracts.

Consider the businessmen meeting at the bar or restaurant, and being overheard while telling a joke or expressing a political opinion. Consider a businessman meeting strangers at a trade show or a plant tour. Consider an expert leading a seminar, presenting a forecast to investors, customers or consultants. Consider a corporate officer speaking at a public board of directors meeting, giving an earnings report or a project update.

Now consider anyone in the audience, even an unrelated stranger nearby, hearing some comment or joke, taking it out of context, and having the power to have that person arrested, and possibly have his career destroyed, as a result.

It happens all the time now, in Western republics once thought of as free countries. Conrad Black, Mark Steyn, Livia Tossici-Bolt, Adam Smith-Connor, and so many more. The list of people arrested, sued or banned for nothing at all grows long – just for talking or writing, or posting or tweeting, or peacefully carrying a sign.

This trend – and this body of anti-speech lawfare – is not conducive to tourism, or to education, or to commerce.

So does the issue have a place in a trade agreement that’s concerned with meetings, correspondence, contract language and constant human interaction? Of course it does.

That so many in the press – and even in the political world – don’t recognize its relevance to a trade agreement just shows how lacking they are in understanding the world that they purport to cover.

Copyright 2025 John F. Di Leo

By Roger Stone and Mark VargasPublished originally in The StoneZONENew York State Attorney General Letitia James is embroiled in yet another scandal – this time involving a charity...

Read moreDetails