By John F. Di Leo, Opinion Contributor

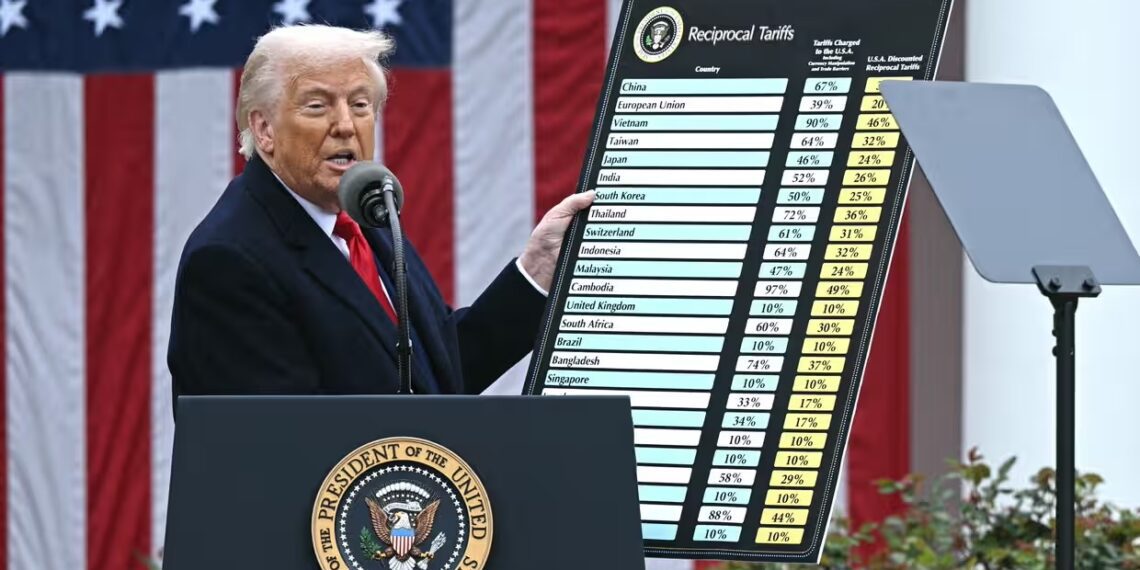

President Trump held his “Liberation Day” press conference on Wednesday, April 2, 2025.

In this presentation, he announced a new additional 10% baseline tariff on top of whatever other tariffs are currently in place (with a few exceptions) for the goods of most countries. For most of our major trading partners, this 10% rate would be replaced by a much higher rate the following week, some as high as 46% (Vietnam) and 49% (Cambodia).

Markets tumbled, perhaps forgetting that with President Trump, most big announcements are his way of beginning a negotiation, so these often terrifyingly high percentages are not likely to remain in place for long.

Each country (or group of countries, in the case of the EU) is invited to negotiate for an improvement to these numbers. We should therefore not expect these shocking tariffs to remain in place at this level. While America’s import tariff burden is likely to be higher at the end of this than it was at the beginning, we should not expect these shocking numbers to remain in place for long, and the hope is that along with their reduction, we will get similar reductions from other countries.

We cannot thoroughly cover a monumental shift like this in a single online article; an enormous amount of important information will therefore be missing from any such column. I will therefore ask you, Gentle Reader, to bear with me as I attempt to address just some of the key items that have been missing from much of the coverage in the first few days since the announcement.

Stackable Tariffs

First, let’s begin with what these are: with just a few exceptions, they are additional tariffs on top of whatever is already in place, hence the term “stackable.”

In the United States, all imported goods are assessed either a Column 1 tariff (our rate on goods made in MFN countries, usually ranging between zero and 20%, depending on the commodity, with the average around 4%) or a Column 2 tariff (our rate on the goods made in Russia, Belarus, North Korea and Cuba), usually ranging between 35% and 60%). So this new country-specific tariff of ten or twenty, or thirty or forty percent is on top of those normal duties.

There are also a number of other taxes assessed on specific imports, depending on the product and the country. We assess an excise tax on imported liquor, very high anti-dumping duties on goods that a foreign country is ‘dumping’ on us at below-cost prices (through proven export-government subsidies), even a 25% special tariff on steel and aluminum (both base products such as rod, plate, sheet, wire and tube, and sometimes even finished goods that include them; a terribly complex body of law).

So these new country-specific “reciprocal tariffs” are on top of almost all of those.

Reciprocal Tariffs

The meaning of the term – reciprocal tariffs – is easy to understand, but difficult to put into practice. In theory, the idea is that we would like to assess the same tariff on a trading partner’s goods that they assess on ours. The challenge is that we all build our trade barriers in very different ways.

The United States government allows most goods – generally speaking, other than foods, drugs, and beverages – to be imported freely into the United States, meaning that the importer needs to pay the aforementioned import tariffs, but there’s usually no approval process involved, and no hoops for the foreign exporter to jump through.

By contrast, many foreign countries have either high tariff barriers or – infinitely worse – high non-tariff barriers, making it extremely difficult for a foreign company’s products to be introduced to their markets. The countries don’t even give their consumers the choice to consider the imported goods, by effectively keeping foreign products out entirely.

Picture a European company offering an electric handheld appliance – say, a power drill or jigsaw – to the American market. Once they find an American distributor or retail chain interested in carrying it, they can start shipping, and the only government process involved is an easy Customs clearance and low import duty payment.

On the other hand, if an American company offers the same kind of electric handheld appliance to Europe, the exporter must first apply through the CE mark process in Europe “to prove its safety” to EU regulators, model by model, and add their mark to the product’s molding. This process alone can cost tens of thousands of dollars per model, before the exporter even knows if he’ll successfully sell any. In addition, Europe places onerous burdens on the bill of material of the products and even their packaging, with complex programs such as REACH, RoHS, PPWR, EPR, and more.

Whether these programs are intentionally meant to be protectionist or not, that’s certainly the result. These foreign countries have programs in place that stop American manufacturers – especially small and midsize ones – from even attempting to enter their market.

As a result, when we look at our trade deficits – how much we export to a specific country versus how much we import from the same country – we cannot assume it’s because our products aren’t competitive or desirable there; we know that at least a part of the reason is that the foreign country’s government has not even given its citizens a chance to consider our products. That’s hardly “free trade.”

In calculating these “reciprocal tariffs,” the Trump Administration looked at these various trade barriers – from tariffs to regulations, from VAT programs to the bottom line import/export differential, and attempted to assign a percentage to it. There’s no way to argue that these numbers are perfect, but on the other hand, there’s no way for the other side to argue that these trade barriers aren’t real, or that they don’t cause a problem deserving some redress.

Why Should We Care?

American manufacturing has taken a terrible hit over the past half century, as American manufacturers have been driven out of business by both the domestic tax-and-regulatory climate and the low taxes and low regulations of many foreign countries. As the years have gone by, the People’s Republic of China (a term difficult to say with a straight face, for a brutal communist regime, therefore commonly called Mainland China or Red China instead) has come to dominate global manufacturing.

The Trump Administration therefore isn’t really just fighting this battle for the United States, but for most of the world. China hasn’t just grabbed manufacturing activity from the United States; they’ve grabbed manufacturing activity from Japan and Mexico, from Europe and Great Britain – and by continuing to dominate the world’s manufacturing capacity, China has robbed other “third world” countries of what ought to be their opportunity to grow along with the global economy.

There is a reason why most of the countries on the world’s “Least Developed Developing Countries” (LDDC) lists of half a century ago are still on that same list today: China has taken an outsize share of the growth opportunities created by the “low cost country sourcing” initiatives of the world’s more affluent economies.

And how has China taken this outsize share? By utilizing tools like currency manipulation, intellectual property theft, and slave labor to keep their products dirt cheap, and to convince Western conglomerates to situate new plants there. China has locked in thousands of companies with thousands of plants, making the western world dependent on their supply chain. If they had done so honestly, it would be another matter, but their labor, taxation and regulatory approaches have served as an immorally unfair advantage, again, hurting not just us in the West, but all the other countries that aren’t corrupt enough or big enough to compete with China’s methods.

The Chinese government has invested heavily in the United States, always in dangerous ways. China has eyes and ears throughout our government, through everything from illegal campaign donations to outright bribery, through plants in congressional offices to active leadership of industry lobbies. We’ve all seen the news reports – Senator Feinstein’s driver, Congressman Swallwell’s girlfriend, Governor Walz’s high school student summer trips, the Biden family’s business associates – and only the tip of the iceberg has even been reported. China has funded/operated school programs and whole schools, designed reciprocal programs with colleges and universities, entered research programs with our own government (such as the NIH under Anthony Fauci).

We need to break China’s growing control of the world, and the United States can’t do it alone; we need to break down the barriers of our major trading partners so that they too can participate – whether they want to or not – in the freeing of the world economy and the growth of other LDDCs at China’s expense.

Does a Trade Deficit Really Matter?

A common libertarian position is that trade deficits don’t matter, because in a free market, everyone should be able to buy what they consider to be the best deal, and the invisible hand will ensure that everyone benefits. The problem with this argument at the moment is that, as we’ve seen above, we don’t have a free market. There are trade barriers all over the place; that horse has left the stable. So the question is how to bring more freedom to the market, and that is a goal with the President’s aggressive tariffs, as unlikely as that may appear.

To look at the question right, we must look at what a trade deficit is, on paper. We will use a traditional economics class example for this study:

Imagine the United States buying two million dollars’ worth of goods from Japan, and Japan only buying one million worth from us. That’s a trade deficit. But what does it really mean? In a closed set, it would mean the US benefited greatly, because Japan is stuck with a million dollar bills – in US currency – that’s useless to Japan until it’s spent somehow.

But it’s not a closed set, is it? South Korea might have the same situation with Japan, and we might have the opposite situation with South Korea. So South Korea will buy stuff from Japan and take on their extra dollars, and South Korea can use them when they buy more stuff from the United States. Eventually, these US dollars have to come back here because they’re useless to the rest of the world until they’re spent in the United States.

For this reason, one could even argue – philosophically – that there’s no such thing as a trade deficit, because the dollars will come back somehow.

But how? How exactly will those dollars come back?

Due to the loss of so much American manufacturing, the above example – perfectly accurate a half century ago – no longer applies.

Today, few countries, if any, have that kind of trade deficit with the United States. For the most part, we buy more physical goods from everybody, than anybody buys from us.

They therefore have to spend their US dollars some other way. They buy American T-Bills, of course, and they buy stocks or bonds in the American markets, but what China in particular has chosen to do, more and more, is to buy American real estate, American politicians, American colleges, and American communities.

Red China doesn’t send the children of its party leaders to American colleges to get a high quality education; they don’t buy up American housing stock because they enjoy paying American property taxes. They do it to increase their influence in changing the kind of country America is, and to increase their power around the world.

China isn’t alone in this; a simultaneous discovery over the past few years has been how certain countries in the middle east, both relative friends like Saudi Arabia and clear enemies like Qatar, have been spending their extra dollars in the USA: building mosques and islamic community centers, partnering with universities to indoctrinate impressionable students and grow either the cause of the global caliphate or the cause of jihad – or both.

All this is enabled – caused outright – by the relative reduction in American manufacturing over these past two generations. If there aren’t things to spend dollars on, people will spend their dollars on something other than things.

And America should be interested in selling its wares, not its soul.

What is a Tariff?

A tariff is a tax. Americans tend to have a different view about tariffs than we do about other taxes, but we really shouldn’t. It’s just a tax, assessed in its own way, as other taxes are assessed in their own ways.

A property tax bill is assessed on a house, business property or apartment building, usually based on its value. An income tax bill is assessed on one’s income – on salary, sales commissions, investment profits and so forth. A poll tax is an identically assessed flat charge for every voter in a society (arguably the only truly “fair” form of taxation). A sales tax is a percentage of the price paid for a domestic goods purchase. And a tariff bill is usually a percentage of the price paid for the purchase of foreign goods.

Some taxes are needed to fund a government. All taxes do damage, by definition – they take money out of people’s pockets and out of the marketplace, so they should be kept as low as possible. But all taxes do damage in a different way; all taxes hit different demographics and affect behavior differently. It’s fair to say we hate all taxes, but it’s not particularly constructive. When governments collect taxes, they are deciding where to meddle and how.

Every Congress and every White House has the opportunity to tweak how the burden of taxation will be distributed. They usually trade off between workers and nonworkers, between individuals and businesses, sometimes between one industry and another. The Trump administration wants to put importers into that mix as a specific demographic. This upends the discussion since America hasn’t thought of it this way in generations, but tariffs are just another tax, which directly hit some demographics harder than others. It’s fair to include them in the discussion, but we have to do so with our eyes open.

Who Pays a Tariff?

Of course, the importer directly pays a tariff. To claim otherwise is silly. The foreign country doesn’t pay it; the company purchasing the imported good pays it. Now, the foreign country should be concerned when the importing country raises tariffs on their goods, because the exporting country will likely lose export sales as a result. But that doesn’t change the fact that the actual immediate payer of the tariff is still the importer. That’s the person who suffers the most. (Even if the exporter offers to “absorb the tax,” he’s still building it into the price charged, so the importer still ultimately pays it).

One of the main hopes of any protectionist tariff, and especially of this one, is that it will encourage much more domestic manufacturing, and discourage a good deal of importing. This is a legitimate and worthy goal, as described above.

However – the program does have two major problems.

First, this isn’t just a battle between American and foreign manufacturing. Most American manufacturing – the manufacture of American machines, cars, appliances, etc – is itself dependent on foreign components.

While the goal is to create a flurry of new American manufacturing activity to replace all that we’ve lost (yes it’s true, we’ve lost at least 90,000 factories and at least five million manufacturing jobs in the past 30 years, while our population has grown by 80 million), the fact is that it takes time to build new factories or to increase existing supply. These new tariffs are hitting today, and the expansions we hope to encourage will occur over the next few years. This means that we are trying to force many American businesses to buy their parts from factories that don’t exist, or won’t exist until two or three or four years after they need the parts. It’s like booking a caterer to host a party this Saturday, but requiring him to do his shopping at a store that went out of business 30 years ago and might, just might, be rebuilt next year. In the meantime, many of these businesses don’t have a choice; they’re being punished with new taxes for an import purchase that’s really out of their control.

And Second, all of American manufacturing is in the same financial condition that the rest of us are in: We’ve all been beaten up by the four horrific years of the Biden-Harris economy.

This past Democrat administration created unprecedented energy costs, outrageous regulatory burdens, and an inflation rate that the nation hadn’t seen since Jimmy Carter, and all that on the heels of the thoroughly destructive Covid shutdowns. The past five years have been a forest fire for American industry. While American businesses may have had the funds to support a costly experiment promising long term benefits five years ago, few American businesses, especially small ones, can afford such an experiment today. The coming tax cuts haven’t even been passed out of Congress yet, but the tariff increases take place immediately.

Many of the very people this program is designed to help – in the long term – will suffer the most, and even go under as a result of it, in the short term. Unless it pays dividends very, very quickly, which it may. Reportedly, while some countries are responding with reciprocal tariff increases; other countries quickly picked up the phone to negotiate.

In the end, this may break open new foreign markets to our exporters while closing existing sources to our importers. And in many cases, those importers and exporters are the same people.

We may not all be inclined to shed too many tears for the American distributor who just imports a cheap shirt or jacket from China and resells it here, but we should be concerned about the hardworking American manufacturers who’ve been forced to buy more and more parts from abroad as their former American suppliers, one by one, have shut their doors over the decades. In many cases, it’s these heroes – these long-suffering American manufacturers – who will be hurt the most before this program bears fruit.

“It’s the Economy, Stupid.”

It’s been over thirty years since this particularly coarse statement burst out in American politics, but it’s always been true. Every election is – to some extent at least – a referendum on the incumbent administration’s economic policies. If this approach takes five years to bear fruit, the Republican party will be turned out of office for a generation. On the other hand, if it bears fruit quickly, to show an economic turnaround, not just by the 2026 midterms but by November, 2025 (when the important statewide elections in New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania and Virginia will be held), then it could usher in a similar period of Republican dominance.

There are so many other macro issues that these subjects affect.

· Manufacturers create not only a living for their employees but satellite support businesses and new career paths for their communities.

· Changes to our trade deficits and a drop in the stock market bubble should bring critical interest rate reductions making everything from home ownership to the national debt more affordable, for both individuals and the nation at large.

· And a host of foreign countries – the aforementioned LDDCs – should gain the opportunity to participate in the global economic pie that China has squeezed them out of until now.

The potential upside of President Trump’s ambitious effort to reorder global trade policy – which has never been attempted before by any other country – is enormous. If it succeeds, thousands of communities, from small town America to our biggest metropolises, will gain a new lease on life. But if it fails, the very people America needs most – our small and midsized manufacturers – could potentially be the first to suffer.

One hopes that the Trump administration would not have gone forward with this program unless they already had negotiations in process with many other countries, and have good reason to expect that many trade barriers will be lifted quickly, enabling the existing American manufacturing community to weather the storm until domestic production rises to meet their needs.

We live in challenging times, far more challenging than they ever had to be, thanks to the horrific economic errors of most administrations (sadly of both parties, but especially Democrats) over the past fifty years.

Copyright 2025 John F. Di Leo

By Illinois ReviewThe Illinois State Rifle Association is urging the U.S. Justice Department to launch an investigation in “The Prairie State” after Attorney General Pam Bondi announced that...

Read moreDetails